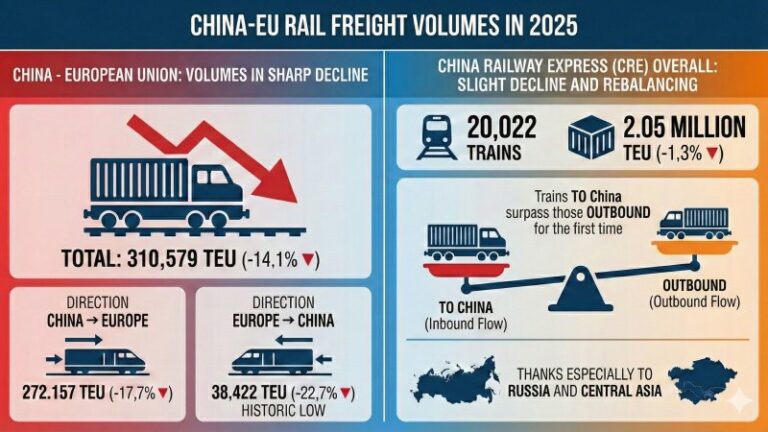

- In 2025, rail freight volumes between China and the European Union dropped to 310,579 TEU, down 14.1%, with a sharper decline both on the China–Europe leg, down 17.7% to 272,157 TEU, and on the return Europe–China leg, down 22.7% to 38,422 TEU, a historic low.

- Overall, China Railway Express reached 20,022 trains, carrying 2.05 million TEU, down 1.3%, with a rebalancing of flows: for the first time, trains heading towards China outnumbered outbound services, mainly thanks to Russia and Central Asia.

- The geography of flows is changing. Central Asia climbed to 1.13 million TEU, up 27.7%, 3.6 times the China–EU traffic. In Europe, Poland concentrates 94% of eastbound flows and Małaszewicze remains a critical hub; the closure of the Poland–Belarus border from 12 to 25 September 2025 blocked around 90% of trains.

Rail freight transport between China and the European Union contracted again in 2025 after the temporary recovery of 2024. Data collected by Upply Market Insights indicate a total of 310,579 TEU, down 14.1% year on year, with declines in both directions: flows from China to Europe fell to 272,157 TEU, down 17.7%, while those in the opposite direction, from Europe to China, dropped to 38,422 TEU, down 22.7%, reaching the lowest level ever recorded within the China–EU perimeter. The result is an imbalance of around 7:1 between outbound and return flows, with impacts on train utilisation, container positioning and cost structures.

The European downturn becomes clearer when viewed within the broader framework of China Railway Express, an international rail system that extends well beyond the China–Europe relationship. According to China State Railway Group data, in 2025 the system operated 20,022 trains, up 3.2%, surpassing the threshold of 20,000 annual services for the first time. Total volumes reached 2.05 million TEU, down 1.3%, corresponding to a cargo value of $67.7 billion (around €62.3 billion). Within this total, the China–EU segment accounts for about 15.1%, while 85% of flows are now absorbed by Russia, Central Asia and other non-EU destinations.

Beyond aggregate figures, what stands out is a shift in balance across the entire system. Eastbound China Railway Express services numbered 9,898, down 6.1%, carrying 1,026,700 TEU (-10.1%), while westbound services rose to 10,124 (+14.4%), transporting 1,023,500 TEU (+9.4%). This is the first time that trains heading towards China have outnumbered outbound services, partially reducing the historic imbalance of the network, but from a European perspective this coexists with the collapse of return flows from the EU. Growth in westbound volumes is driven mainly by cargo from Russia and Central Asia, not from the European market.

Within the China–EU corridor, 2025 is therefore a year of contraction and, at the same time, of geographical redistribution of Eurasian rail demand. The main drivers are economic and linked to modal competitiveness. Upply Market Insights connects the downturn to lower maritime freight rates following the exceptional conditions of the Red Sea crisis, when in 2024 Houthi attacks pushed up shipping costs, making rail more attractive as a compromise between time and cost. In 2025, the economic advantage of rail has weakened as the gradual, though not yet fully consolidated, normalisation of routes and smoother supply chains have favoured maritime transport.

An assessment by TopChinaFreight summarises the competitive pressure well. For a 40-foot High Cube container, sea freight rates are indicated at $3,000–4,000 (around €2,760–3,680) with transit times of 30–45 days, while rail transport for the same unit can cost $10,500–12,500 (around €9,660–11,500) with transit times of 15–20 days. Rail retains a time advantage, but under “normal” market conditions the cost differential widens again, narrowing the range of suitable goods to those with high unit value, rapid turnover or tighter planning requirements.

Alongside economic factors, 2025 highlights operational risk linked to the concentration of European access points. Upply Market Insights notes that in the first half of 2025 Poland accounted for 93.4% of eastbound traffic into the EU, rising to 94% by year-end, with Małaszewicze, the Polish terminal on the Belarus border, alone handling around 90% of China–Europe trains. This configuration leaves the northern route via Russia and Belarus vulnerable to geopolitical shocks and border measures. This was clearly illustrated by the closure of crossings between Poland and Belarus from 12 to 25 September 2025, reportedly triggered by the incursion of Russian drones into Polish airspace during the Zapad-2025 exercises. Everstream estimates that the closure paralysed around 90% of China–EU rail traffic for thirteen consecutive days. Such disruptions undermine service credibility, translating into rescheduling, terminal congestion and indirect costs linked to inventory and punctuality.

At the same time, growth within China Railway Express is shifting decisively towards Central Asia. Upply Market Insights attributes 1.13 million TEU to this corridor in 2025, up 27.7% year on year, carried by 14,254 trains (+9.6%). Volumes are now 3.6 times those of the China–EU corridor, making Central Asia the main growth basin for rail within the system’s Eurasian footprint. This shift is consistent with demand for raw materials and energy towards China and with infrastructure investments linked to the Belt and Road Initiative.

This geographical reconfiguration also affects hubs. Xi’an confirmed its position in 2025 as the leading Chinese node of China Railway Express, with 6,037 trains (+21.1%), representing around a quarter of national services. The hub also recorded growth of 60.6% towards Central Asia, another sign of priority being given to Central Asian routes. Operationally, Xi’an reports loading and unloading capacity of around 50 trains per day, annual capacity of 1.2 million TEU and eighteen international routes to Europe, Russia, Central Asia and South-East Asia. In November 2025 it launched full timetable services with fixed schedules, including Xi’an–Prague in eleven days and four hours, compared with eighteen days for conventional trains. Schedule standardisation aims to reduce variability and facilitate logistics planning, a crucial issue when flows are exposed to border risks.

Alashankou, also known as Alataw Pass, has become the main border rail hub between China and Kazakhstan. In 2025 it handled 8,165 trains, up 6.3% year on year. It is the first hub to exceed 8,000 services, with an average of 21 trains per day and peaks of 30. Xinhua reports customs clearance times below sixteen hours, down 18.4% on 2024, and reloading times for return trains of around two hours. Alashankou also has a technical role as a break-of-gauge point between Chinese standard gauge and broad gauge, requiring transhipment operations that, according to Cceeccic, have been optimised to around two hours per train.

Returning to China–Europe traffic, the imbalance of return flows from Europe to China remains the most critical issue for the sustainability of rail transport. In particular, there is a weakening of European automotive exports, linked to difficulties in the German industry, traditionally a major rail user. In the first half of 2025, rail shipments from Germany to China collapsed by 26%. This drop, affecting vehicles and components, mirrors the fall in German car sales in China, which hit a thirteen-year low.

In the opposite direction, Chinese exports of vehicles and high-value components have increased. The cargo mix includes textiles, furniture and household appliances, but also photovoltaic panels, electric vehicles and lithium batteries. For European operators, this means rail continues to capture certain time-sensitive, high-value supply chains, but with weaker return flows and therefore greater complexity in managing container cycles and building stable tariffs.

The search for alternatives to the northern route is another structural feature of 2025. On the Trans-Caspian corridor, also known as TITR, 371 trains ran in the first ten months of 2025, up 30% year on year. Added to this are the Middle Corridor and, for other basins, the New Western Land–Sea Corridor towards South-East Asia, which reached 1.425 million TEU in 2025, up 47.6%. While these are not equivalent corridors for access to the EU, the figures point to a system increasingly oriented towards a more polycentric network, able to absorb demand even when Europe becomes riskier or less profitable.

In the short term, certain niches may support China–Europe rail demand despite the overall downturn. In December 2025, a major Shein logistics centre near Wrocław, Poland, developed by Glp, became operational as a primary European distribution hub. The logic of cross-border e-commerce, more sensitive to transit times than other cargoes, can create opportunities for rail when 15–20 day transit times fit inventory planning better than the 35–45 days typical of maritime transport. In parallel, initiatives on fixed schedules and cooperation agreements announced at the Second China Railway Express Cooperation Forum in Xi’an, with over one hundred agreements and seven new fixed-timetable services reducing transit times by more than 30% on average, point towards greater service reliability.

Overall, 2025 shows a China–EU rail market losing volumes and modal share due to cost factors and corridor risks, while China Railway Express as a whole maintains its scale and strengthens its centrality in relations with Central Asia and, more broadly, in imports into China. For the European market, the key variables remain route reliability, concentration of entry nodes and the ability to generate competitive return loads. Border risk management, the evolution of maritime freight rates and European demand will continue to shape modal choices along the Eurasian axis into 2026.

Michele Latorre