When people say that Europe is rearming, it does not merely refer to the purchase of weapons or the strengthening of conventional military forces. The phenomenon also encompasses civilian transport infrastructure, which is gradually being adapted for dual use, moving beyond the traditional approach of separate facilities for commercial and military operations. This transformation is already underway and appears to be progressing systematically and in a coordinated fashion, at least across northern and eastern Europe. The financial driver behind it is the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility, which has allocated €1.75 billion for military mobility projects, with a target of reaching €75 billion by 2030. The Netherlands, Germany and Poland are at the forefront of this effort.

In this context, the European Commission has identified over 500 critical infrastructure points requiring upgrades to support military mobility. These include ports, airports, railway bridges, tunnels and transport corridors that must be adapted to allow the rapid passage of heavy and oversized military equipment. This is not a brand-new initiative: the Military Mobility Action Plan 2.0 was launched in November 2022 and builds on an earlier plan from 2018. However, the war in Ukraine has hastened its implementation.

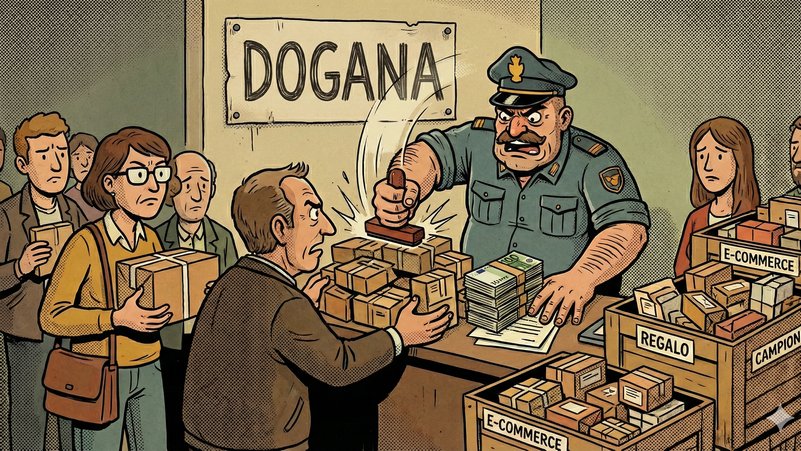

The plan focuses on four main actions: upgrading infrastructure through improvements to the Ten-T corridors to support large-scale troop and equipment movements; simplifying regulations by digitising customs and logistics procedures; enhancing resilience to protect systems against hybrid, cyber and climate-related threats; and boosting connectivity by strengthening links between countries.

On the maritime front, where the CEF has allocated €145 million, the cornerstone of this network is the port of Rotterdam. It is considered a key NATO hub for projecting military forces towards the alliance’s eastern flank. Its conversion to dual use includes the designation of specific berths for NATO military vessels, the adaptation of container terminals to safely handle ammunition, coordination with the port of Antwerp for high-volume traffic and the scheduling of regular amphibious drills.

In an interview with the Financial Times, the CEO of the Port of Rotterdam Authority, Boudewijn Simons, confirmed that space is being reserved for military vessels and that coordination is underway with neighbouring ports to handle the arrival of British, American and Canadian vehicles and cargo. He added that military ships could dock at the port four or five times a year, while the surrounding logistics network can be adapted for the storage of supplies such as medical equipment, critical raw materials, energy systems, shelters and, if needed, food and water.

Another strategic hub is the port of Hamburg, also designated to support NATO’s eastern front. This role is part of a €1.1 billion investment plan to improve container terminals and expand yard areas. The port's manoeuvring basin will also be widened from 480 to 600 metres to accommodate larger vessels. On the strictly military side, Hamburg hosts Red Storm Alpha exercises, with around a hundred troops deployed to secure port infrastructure.

Further east in Poland, the port of Gdynia is being equipped to become the Baltic’s military gateway. Investments are underway to boost cargo handling and adapt certain facilities for dual use. Additionally, the port is implementing a drone system to manage traffic, monitor the area and counter other autonomous aircraft. In 2023, Gdynia carried out a significant dual-use operation by transferring American military equipment.

Alongside these three pillars, other North Sea ports are deemed strategic. One is the aforementioned port of Antwerp, already serving as a hub for US military operations in Europe and now increasingly coordinated with Rotterdam. In the Netherlands, the ports of Vlissingen and Eemshaven received shipments of US armoured vehicles in October 2024. Returning to Poland, the port of Swinoujscie also plays an important role, particularly as a liquefied natural gas terminal.

The second major strand of European investment involves rail transport, which receives nearly half of the CEF funding for military mobility—around €874 million. The Netherlands has increased its fleet of specialised wagons by 20 percent, acquiring 75 units for transporting military equipment in containers. This initiative fits into Germany’s large-scale rail network upgrade programme, which is essential for moving equipment from Atlantic ports to the eastern front.

The rest of the CEF funding earmarked for dual-use infrastructure includes €548 million for road networks, accounting for 31 percent of the total, €164 million for air infrastructure (10 percent) and €16 million for inland waterways (1 percent). The entire budget for the 2021–2027 period has now been allocated, and no guidelines have yet been issued for the following phase, from 2027 to 2030.

In addition to EU funding, further resources are being provided by national programmes and NATO. The alliance has allocated about €4.6 billion through its Security Investment Programme, primarily focused on maritime infrastructure. Key investments include €2.4 billion in maritime facilities in 2024, including €300 million for projects in Souda Bay, Greece; €550 million for naval refuelling infrastructure; and €190 million for port upgrades at the Rota Naval Station in Spain.