US tariffs continue to navigate the sea of uncertainty following the Washington Court of Appeals decision deeming most of them illegal. According to the judges, whilst it is true that the law confers significant authority upon the president to undertake a range of actions in response to a declared national emergency, none of these actions explicitly include the power to impose tariffs, duties or similar measures, nor the power to tax. The issue revolves around the Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, which allows the president to bypass Congressional voting in cases of "unusual and extraordinary" threats. However, the Court clarifies that this does not grant the president unlimited authority to impose tariffs.

The judges have nonetheless decided that all current tariffs remain in force until 14th October 2025, to permit an appeal to the Supreme Court, which will have the final say on the matter. Attorney General Pam Bondi has already announced the appeal. Should the Supreme Court judges confirm their Appeal Court colleagues' verdict, not only will the vast majority of tariffs be annulled, but the trade agreements drawn up by the United States with various countries (including the European Union) under the threat of tariffs will be undermined.

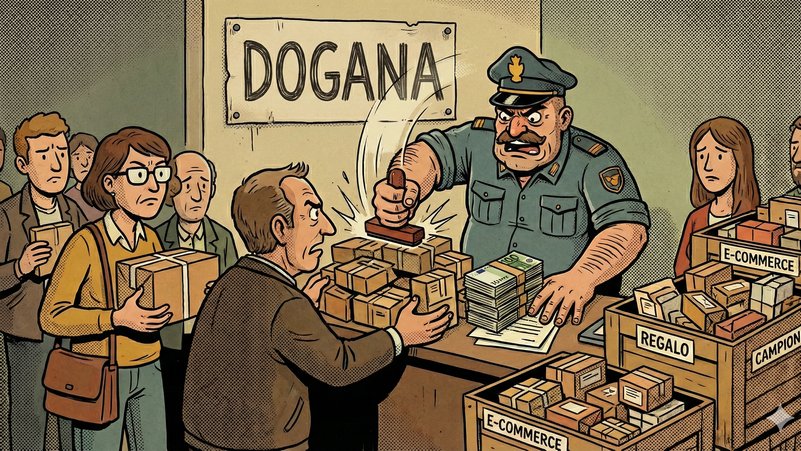

There is no doubt, however, regarding the abolition of the de minimis rule, namely the exemption from tariffs for packages valued up to 800 dollars, which came into effect on 29th August 2025. All previously exempt shipments now require formal customs declaration. This includes providing the 10-digit Harmonised Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS) code for each product, necessary for correct tariff application, representing an enormous increase in administrative burden. The new regime differentiates between postal and commercial shipments.

For international postal shipments, a six-month transitional system has been introduced (until 28th February 2026), during which senders can choose to pay a flat-rate "specific duty" ranging from 80 to 200 dollars per item (depending on the IEEPA tariff rate of the country of origin) or the standard "ad valorem" duty based on product value. The creation of this temporary fixed-rate system is an implicit admission that the global postal system is technologically and operationally incapable of managing the immediate transition to a complete ad valorem tariff regime. This is therefore a stopgap measure to prevent total collapse of the postal channel, revealing a critical vulnerability in global logistics infrastructure that the de minimis rule had masked.

The impact has been immediate: following the suspension on 2nd May, valid only for China and Hong Kong, the volume of low-value packages from the region collapsed by 85 per cent, from approximately 4 million to 600,000 daily shipments. E-commerce companies such as Temu and Shein must either absorb the new costs, eroding their thin margins, or pass them on to consumers, undermining their main value proposition based on ultra-low prices. However, US consumers are also penalised (and perhaps primarily so), having to pay higher prices for imported goods whilst waiting longer for them.

A 2024 document from the National Bureau of Economic Research concluded that de minimis was a "pro-poor trade policy". The study found that shipments to the lowest-income postal codes were subject to the lowest average tariffs before the suspension, a balance that now reverses, with their tariff burden expected to rise to nearly 12 per cent. The elimination of the exemption is estimated to reduce consumer welfare by up to 13 billion dollars annually, with low-income and minority consumers bearing a disproportionate share of this cost.

Companies based in the United States that source domestically or already pay tariffs on wholesale imports should benefit instead. By removing the cost advantage of foreign direct sellers, the policy aims to make American manufacturers and retailers more competitive. Companies operating in US Foreign-Trade Zones will also benefit, as the policy eliminates a disparity that previously encouraged shifting activities overseas.

The abolition of de minimis is having repercussions on the logistics supply chain as well. Postal companies in many countries have temporarily suspended parcel shipments to the United States. Instead, major express carriers such as FedEx, UPS and DHL, which already have robust customs brokerage infrastructures, are better equipped, but at a cost to senders. These carriers are now responsible for collecting duties and submitting formal declarations for all low-value shipments. In response, they have introduced new charges and increased existing ones. For instance, both UPS and FedEx increased their international processing fees before the suspension. Senders now face a range of potential new charges, including those for declaration preparation, brokerage and goods processing, which can add substantial costs beyond the duties themselves.

This means that the previous model of shipping individual packages by air is becoming economically unsustainable for many products, favouring cargo consolidation. Companies are now incentivised to shift from air parcels to maritime bulk transport, importing goods into the United States in containers. This requires a transition to pre-positioning inventory in US warehouses or utilising third-party logistics providers for domestic distribution. This model allows duties to be calculated on the lower production cost rather than the higher retail price, thus reducing the effective duty rate.

The new regime also imposes enormous demands on data and technology. Each shipment now requires accurate HTS code classification, value verification and electronic declaration submission. Manual workflows are no longer scalable to handle the massive volume of previously exempt packages. This creates an urgent need to invest in automated compliance solutions, including software for HTS classification, duty calculation and streamlined customs declaration submission.