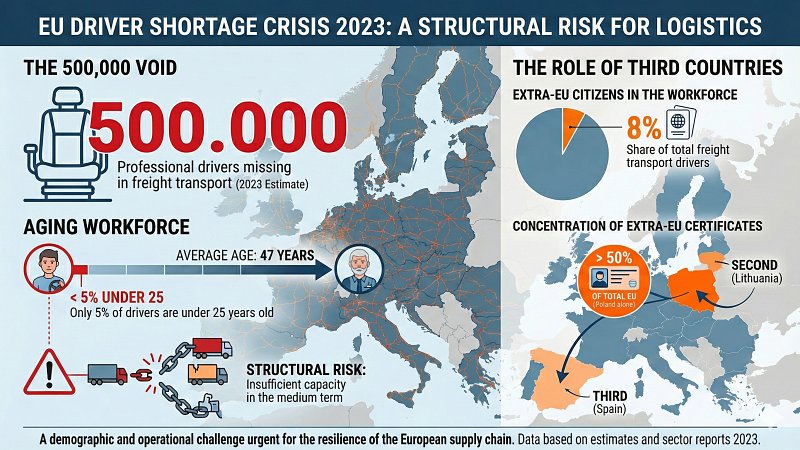

A report published by the European Union on the activity of non-EU immigrants in EU road haulage companies shows that, due to the shortage of young local workers, the number of staff arriving from third countries is increasing. Brussels estimates that they now account for 8% of all heavy goods vehicle drivers, and their share is continuing to rise. However, the report also highlights several critical issues, including the cost of recruiting non-EU drivers.

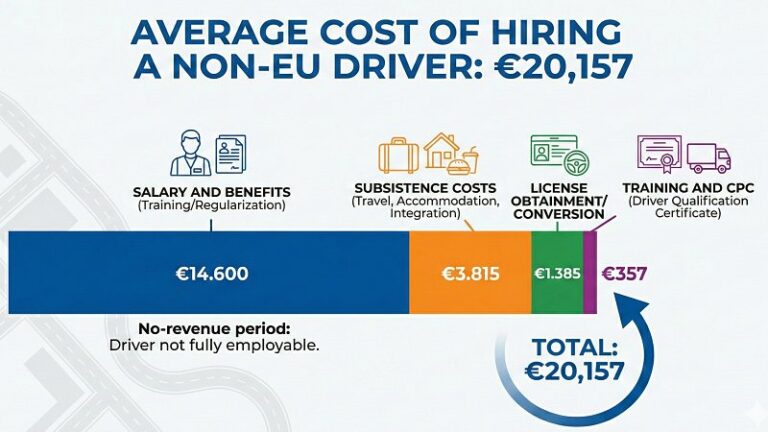

According to research conducted by the report’s authors through company interviews, the average cost of onboarding a single non-EU driver is 20,157 euros. The largest component is wages and related charges paid during the training and regularisation period, amounting to 14,600 euros. During this time, the driver cannot yet be fully deployed in transport operations and therefore does not generate revenue for the company. This is followed by subsistence costs, estimated at 3,815 euros, including travel from the country of origin, accommodation and initial integration expenses. Obtaining or converting a driving licence in an EU Member State entails an average cost of 1,385 euros, while training and obtaining the Driver Certificate of Professional Competence (CPC) adds a further 357 euros.

The report notes that 90% of transport companies are micro-enterprises with fewer than ten employees. In this context, an initial investment of more than 20,000 euros per driver can have a significant impact on corporate liquidity. Larger companies, by contrast, generally have in-house administrative and legal structures capable of managing complex procedures and better absorbing periods of inactivity. As a result, the recruitment of non-EU drivers is taking place mainly within more structured operators.

The length of procedures is another critical factor. The international recruitment process takes on average between four and six months, with peaks that can reach up to a year, due to the fragmentation of responsibilities among national authorities, consular bodies and training institutions. The timeline analysis in the report shows that the issuance of professional documents, such as the Driver Certificate of Professional Competence and the driver card for the digital tachograph, accounts for a relatively limited portion of the overall timeframe, while visa and residence permit procedures represent the longest and most uncertain phase.

A particularly critical issue is the so-called regulatory paradox linked to the Driver Certificate of Professional Competence. In several Member States, normal residence of at least 185 days is required to enrol in qualification courses. However, in order to obtain a residence visa, it is often necessary to have an active employment contract, which in turn presupposes possession of the professional certificate. This mechanism creates an administrative loop that delays drivers’ entry into the labour market and prolongs the period in which companies incur costs without being able to deploy the driver operationally. To address these issues, Brussels has launched a legislative process aimed at simplifying administrative procedures and facilitating the training pathway, which also includes obtaining the CPC.

M.L.