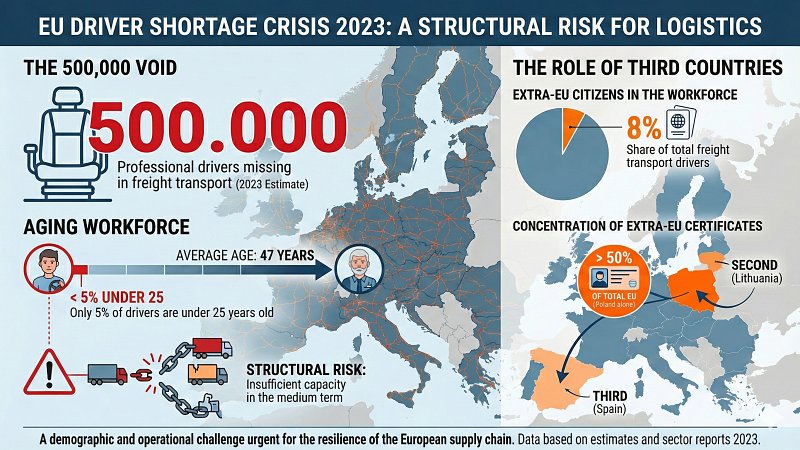

A report published in February 2026 by the European Commission highlights the growing contribution of non-EU personnel to the driving of heavy goods vehicles. This trend reflects the shortage of young Europeans willing to replace retiring generations. Beyond outlining the current situation, the report also looks ahead to the regulatory changes the Union plans to introduce in the coming years to tackle the driver shortage.

One of the most significant measures concerns the system for recognising driving licences issued by third countries. The reform introduces Code 72, which will progressively replace Code 70, currently used in many licence conversion cases. Code 70 often entails an operational restriction linked to the Member State that carried out the licence exchange, limiting the driver’s cross-border mobility. By contrast, the new Code 72 will certify that the non-EU licence meets EU standards, allowing drivers to operate in all Member States without having to retake theoretical or practical tests when relocating. For freight transport companies, this will translate into greater flexibility in allocating labour across the European market.

The legislative cornerstone of this transition is Directive EU 2025/2205, which establishes a common framework for assessing drivers from non-EU countries. Member States will have until November 2029 to adapt their national motoring authority systems and databases to ensure full recognition of Code 72 across the entire territory of the Commission. The Directive also introduces minimum criteria for including third countries on a European list of States whose training standards are deemed equivalent, paving the way for more automatic recognition of qualifications.

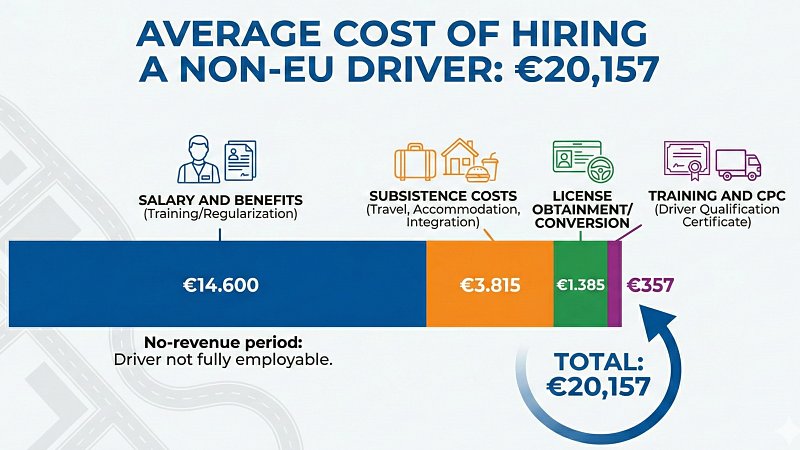

At the same time, the report highlights the revision of Directive 2003/59/EC on the initial qualification and periodic training of drivers. The reform aims to remove the administrative bottleneck created by the current residence requirement for access to Driver Certificate of Professional Competence courses. At present, the average time needed to obtain the certificate can reach eight to ten months, partly due to the sequential process involving visa issuance, residence registration and the start of training. Following the reform, the objective is to reduce this pathway to three to four months by allowing training to run in parallel with entry procedures rather than consecutively. For companies, this would mean shortening periods of inactivity and reducing financial exposure linked to onboarding staff.

A further regulatory element is the EU Talent Pool, a European digital platform designed to match labour supply and demand in a transparent and verified way. According to the report, access will be reserved for companies that meet specific ethical and pay standards, with the aim of limiting the use of informal channels and reducing the risk of unfair recruitment. The system will enable Authorities to monitor entry flows by sector, linking migration quotas to the actual needs of the freight transport industry.

The roadmap envisages an initial transposition phase for Directive 2025/2205 in the 2024–2025 period, followed by the technical implementation of the EU Talent Pool and the first harmonised bilateral agreements between 2026 and 2027. In November 2029, the general obligation to recognise Code 72 across the Union will enter into force.

Overall, the regulatory evolution outlined marks a shift from a national and fragmented system to a more integrated European model. For freight transport, this implies greater mobility for non-EU drivers between Member States, shorter administrative timelines and a more structured selection of third countries with equivalent training standards. The effectiveness of this transition will depend on the ability of Member States to coordinate databases, controls and procedures, ensuring that differing national practices do not continue to create competitive imbalances within the internal market.

M.L.