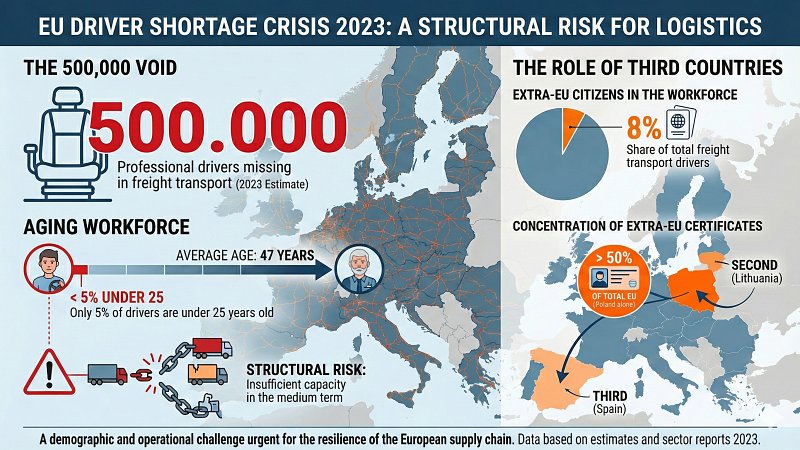

According to the European Commission’s report on the use of non-EU personnel to drive heavy goods vehicles within the European Union, this trend is steadily increasing in response to the lack of young Europeans willing to replace the large cohort of drivers who will retire in the coming years. The shortage is already estimated at half a million drivers. An important dimension of this phenomenon is its social impact, particularly the risks of exploitation and the level of social protection afforded to third-country drivers employed in road freight transport. The picture that emerges is complex: on the one hand, there is a formally robust European regulatory framework; on the other, vulnerabilities remain due to bureaucratic complexity and the limited transparency of recruitment channels.

Directive EU 2024/1233 establishes that, once the single permit has been obtained, a non-EU driver is entitled to the same conditions as nationals of the host Member State in terms of pay, working conditions and access to social security. This includes compliance with national minimum wages or applicable collective agreements, full protection in matters of health and safety, and the right to freedom of association, including the right to strike and to join representative organisations.

However, the report highlights that the moment of greatest vulnerability lies in the pre-contractual phase, between the search for employment and the formalisation of the contract. During this period, the worker does not yet benefit from the full protections provided by the labour law of the Member State, but may already have incurred significant costs or entered into financial commitments in the country of origin. The lack of clear and centralised information on pay conditions, professional requirements and administrative procedures encourages reliance on informal channels.

The Road Transport Due Diligence 2023 study shows that, of 166 third-country drivers interviewed, the majority found employment through social media or non-institutional personal networks. This suggests a correlation between the use of unverified intermediaries and the risk of abusive practices, such as undue commissions or misleading information about employment conditions.

Non-EU immigrant status therefore exacerbates a context that already shows exploitation of drivers from other EU Member States, as evidenced by the steady stream of investigations conducted in several countries. In addition to employment-related blackmail, there is the added threat of expulsion. Of course, the recruitment of migrant workers does not always involve illegal conduct, but given that the European Commission’s report estimates that non-EU drivers already account for eight per cent of the total, it is clear that they now represent a fundamental component of European logistics. To ensure fair competition between companies, monitoring the legality of employment relationships must remain constant.

M.L.