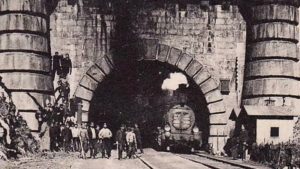

On 26 December 2025, the Fréjus rail tunnel will turn 155. On the same day in 1870, the final diaphragm was broken through, a date considered the milestone of this work, which at the time represented an almost daring technical challenge, marked by one record after another. One figure is enough: only nine months elapsed between the completion of excavation and the opening to traffic. Beyond being a pioneering project, as the longest tunnel in the world at 12,234 metres, it was a gamble that many considered lost from the outset because it lay at the limits of the possible. Only the determination of the government led by Count Cavour and the extraordinary capability of the Savoyard civil engineering corps made the undertaking feasible.

The initial assumptions could only support the sceptics. With the construction techniques known at the time of design, the works were estimated to take 36 years. Thanks, however, to the prodigious development of new and revolutionary compressed-air drilling machines, the project was completed in just 14 years. This led to a curious outcome: France, which at first had sought to protect itself by imposing a penalty in the event of delays, ended up having to pay a substantial bonus for the more than 15 years saved.

Two further extraordinary facts deserve mention. The first concerns the start of the works, inaugurated by King Victor Emmanuel II just fifteen days after approval of the law authorising the project, something inconceivable under today’s regulations. The second is the extremely high level of precision achieved at a time when there was neither laser technology nor GPS. After the final diaphragm was broken through, almost at the midpoint of the tunnel, a discrepancy of just 40 centimetres in alignment and only 60 centimetres in height was recorded.

Today, however, the Fréjus tunnel and railway show all of their 155 years of history. This affects both passenger transport, where fast connections are now expected, and freight traffic, which requires large-gauge trains of standard length and with significant trailing loads, something impossible with a single locomotive. Hence the need to build a new Turin–Lyon route, whose essential turning point is the 57.5-kilometre base tunnel beneath Mont Cenis.

The anniversary of 26 December provides an opportunity to review the works under way, both on the surface and underground, where 18 excavation faces are active. By the end of October 2025, total tunnel advance had reached 45.3 kilometres, or 27.7% of the overall total, including 19.2 kilometres in the Mont Cenis base tunnel. In Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne, works have included the installation of long welded rails for the four main running and passing tracks between the bridges over the Arvan and the Arc. Four kilometres further east, at the Saint-Julien-Montdenis site, activities continue both on the final lining of the southern bore at the French portal of the base tunnel and on conventional excavation of the two bores.

At Saint-Martin-la-Porte, the tunnel boring machine Viviana is in its “learning” phase, advancing slowly to calibrate systems and complete commissioning. In parallel, excavation continues on the La Praz platform, starting from the logistics tunnel of the even and odd bores of the base tunnel, with a symbolic milestone reached by the blast: the thousandth since the start of works. At the Villarodin-Bourget site, while outfitting of the cavern continues in preparation for assembling the TBM, the first kilometre of tunnels built between the base tunnel and the logistics tunnels has been completed.

On the Italian side, at Chiomonte, the works required to start conventional excavation of the initial section of the Maddalena 2 gallery have been completed. Finally, in the area of the future interconnection tunnel site, the first works have begun on the section linking into the historic line and the Bussoleno railway station.

Piermario Curti Sacchi