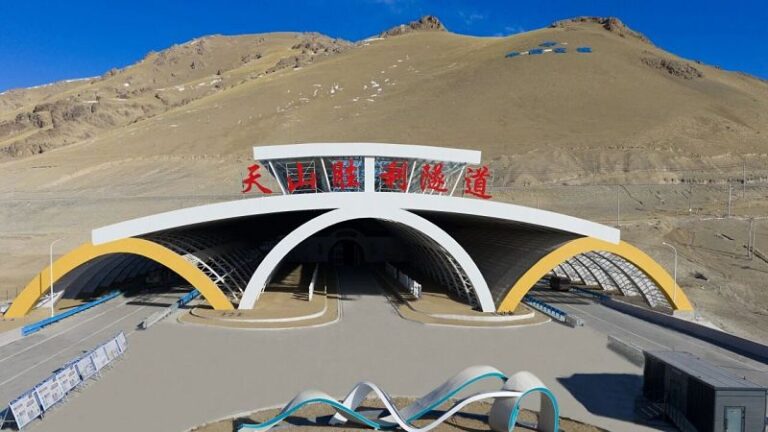

On 26 December 2025, the Tianshan Shengli road tunnel was officially opened in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. With a length of 22.13 kilometres, it becomes the longest motorway tunnel in the world. The structure cuts through the Tianshan mountain range and represents the technological core of the G0711 Urumqi–Yuli expressway, a strategic 324.7-kilometre corridor built with a total investment of 46.7 billion yuan, equivalent to around €5.668 billion. The work was carried out by China Communications Construction Company Limited.

The project was driven by the need to overcome one of Xinjiang’s main infrastructural bottlenecks, where road links between the Junggar Basin in the north and the Tarim Basin in the south were constrained by mountain passes subject to seasonal closures. With the tunnel now in operation, crossing the Tianshan range takes around twenty minutes, compared with the several hours previously required.

From a structural perspective, the Tianshan Shengli is designed as a complex underground system based on what engineers termed the “three tunnels plus four vertical shafts” scheme. Two parallel main tunnels carry vehicular traffic on a total of four lanes, built to motorway standards with a design speed of 100 km/h. Between them runs a third central service tunnel, dedicated to safety, rescue operations, maintenance and plant systems.

This configuration separates traffic flows from support infrastructure, improving emergency management and reducing operational risks in a tunnel of exceptional length. Regularly spaced cross passages between the three tunnels allow rapid evacuation of users and access for emergency services in the event of an incident.

The alignment reaches a maximum overburden depth of 1,112.2 metres below ground level. Along this stretch, the project includes four vertical shafts, which were crucial both during construction and for the operation of the infrastructure. Shaft number two, with a depth of 707 metres, is the deepest ever built for a motorway tunnel. According to the designers, these shafts play an essential role in ventilation, smoke extraction in the event of fire, emergency access and the transport of materials and personnel.

Tunnel excavation required the use of advanced boring technologies, particularly for the central service tunnel, which was driven by two large-diameter full-face tunnel boring machines designed and built in China. The TBMs, named Tianshan and Shengli, are 282 metres long, weigh around 2,000 tonnes and have an excavation diameter of 8.43 metres. Each machine is equipped with 58 rotating cutters and was engineered to operate in highly variable geological conditions.

The two TBMs worked simultaneously from the northern and southern sides of the mountain range, advancing towards the centre of the massif. Average excavation rates ranged between 15 and 20 metres per day, with a peak of 33.16 metres in a single day and a monthly record of 528 metres. Project data indicate that the use of these machines achieved advance rates five to seven times higher than traditional drill-and-blast methods.

Alongside mechanised excavation, a key role was played by the construction strategy known as “long tunnel, short excavation”. Thanks to the vertical shafts and cross passages, the number of working faces was multiplied, moving beyond the two main portals to numerous intermediate excavation points. At certain stages of the works, up to seven excavation faces were active simultaneously, with more than 1,200 workers and hundreds of machines operating daily. This organisation reduced the overall construction time to 52 months, compared with the original estimate of 72 months.

Geological conditions proved to be one of the most critical aspects of the entire project. The tunnel crosses 16 geological fault zones, characterised by alternating hard rock, friable materials and sections subject to high geostatic pressures. In some areas, rock stress reached values of 21.8–22 megapascals, with the risk of sudden and violent rock bursts. Elsewhere, particularly along the F-6 fault zone, water inflows exceeding 10,000 cubic metres per day were recorded, according to technical reports released during construction.

Environmental conditions added further complexity. The site lies at an average altitude above 3,000 metres, with a mean annual temperature of –5.4°C and minimum temperatures falling to –41.5°C. Reduced oxygen levels and working windows limited by weather conditions affected shift organisation and the design of systems to support the workforce.

From a structural and systems standpoint, the tunnel was designed to ensure high safety standards. The infrastructure incorporates a ventilation system sized for the record length of the tunnel, firefighting networks with water curtains and misting, fire detection sensors and an extensive network of emergency connections. There are 81 pedestrian escape routes and 30 vehicular escape routes, as well as five rescue stations capable of intervening within five minutes from any point in the tunnel.

Operations are managed through a digital platform based on the digital twin concept. A virtual replica of the entire infrastructure allows real-time monitoring of structural conditions, systems and traffic, integrating data from around 1,000 cameras and 50,000 control devices. The tunnel is fully covered by a 5G network, built to support continuous data transmission and operational coordination.

Particular attention was paid to environmental protection during construction. The western alignment was selected to minimise impacts on glaciers, high-altitude grasslands and watercourses. Three wastewater treatment plants, two inside the tunnel and one outside, enabled 100% reuse of treated water in compliance with national Class II surface water standards.

Pietro Rossoni