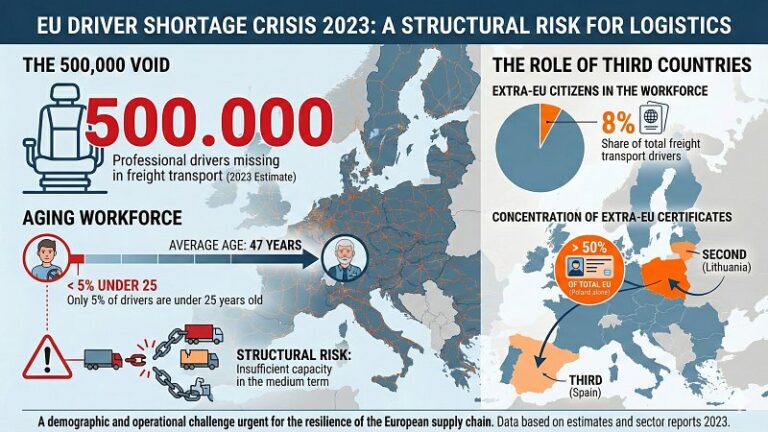

- In 2023, the European Union faced a shortage of around 500,000 professional freight drivers. The average age reached 47, and only 5% of drivers were under 25. This trend exposes logistics to a structural risk of insufficient capacity in the medium term.

- Third-country nationals account for around 8% of the freight transport workforce, with a strong geographical concentration. Poland alone holds more than half of the active driver attestations in the EU, followed at a distance by Lithuania and Spain.

- The driver attestation, provided for under Regulation (EC) No 1072/2009, is the key regulatory tool for employing non-EU drivers in international transport. However, the absence of an obligation to return expired documents makes it difficult to determine precisely how many are actually in use.

In 2023, road freight transport in the European Union recorded an estimated shortage of around 500,000 professional drivers, according to the European Commission report on non-EU immigrants in road transport 2026, published in February. The issue affects the entire European market, impacting supply chain continuity and unfolding against a backdrop of a progressively ageing workforce. The authors confirm previously reported figures, including a high average age of 47, above that of the overall EU population at 44.4 years, and a very limited share of young drivers, with only 5% under 25. Generational renewal is therefore constrained, with few exceptions such as the Netherlands, where the share of workers under 25 reaches 13% thanks to training pathways starting at the age of 16.

In this context, the recruitment of third-country nationals has become a structural component of the system. The report states that non-EU drivers account for around 8% of the freight transport workforce, a higher proportion than in the passenger segment. In absolute terms, between 237,000 and 300,000 third-country drivers are currently estimated to be active in road haulage. The authors stress that without this contribution, the sector’s operational capacity would contract significantly.

The report explains that the key instrument for tracking lorry drivers is the driver attestation, a document certifying the lawful employment of a driver in a Member State where the undertaking is established. The attestation belongs to the company rather than the driver and has a maximum validity of five years, a constraint that strengthens the link between worker and employer and allows operations in international transport. At the end of 2022, 302,526 driver attestations were in circulation in the EU. However, there is no general obligation to return expired attestations, making it difficult to determine the actual number of active documents and, consequently, to quantify precisely the number of non-EU drivers effectively employed.

Current data nonetheless clearly show an upward trend, as the issuance of attestations over time reflects a marked increase in recourse to this instrument. Between 2014 and 2018, the number of attestations rose by more than 25% annually. From 2018 to 2022, growth moderated, with a 9.2% increase in the last observed year, in a context shaped by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The slowdown does not indicate a reversal of the trend, but rather a phase of consolidation after rapid expansion.

The geographical distribution of attestations highlights a strong concentration of non-EU drivers in a limited number of countries. At the end of 2022, Poland accounted for 160,664 attestations, followed at a distance by Lithuania with 66,073, Spain with 22,895 and Slovenia with 13,827. The gap with other large countries is significant: Italy stood at 2,619 attestations, while France recorded only 63. The concentration in a handful of Member States points to markedly different national models in access to non-EU labour, but also to a differing distribution of international road haulage fleets, which are the main employers of third-country drivers.

Poland represents the principal European hub for recruiting third-country drivers. At the end of 2023, it employed around 162,489 non-EU drivers in freight transport. To facilitate entry, the country applies simplified procedures for certain nationalities, including Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, allowing employment for up to 24 months without a full work permit. This approach reduces recruitment times to an estimated four to six weeks, compared with six to 12 months in other Member States. Lithuania also adopts a speed-oriented model: the report notes a high use of temporary tachograph cards, accounting for 2.6% of the total issued, against a much lower EU average. This instrument makes it possible to accelerate the entry of third-country drivers into truck cabins.

At the other end of the spectrum are countries with more restrictive requirements, mainly in Western Europe. The Netherlands stands out, with only 49 attestations active for third-country drivers in mid-2024, due to a system that issues work permits only in the absence of EU candidates. Denmark requires minimum salaries for work visas of around €52,650 per year, a threshold that effectively limits access for many non-EU drivers.

Spain, meanwhile, has developed an intermediate model. In its freight transport sector, around 7% of drivers’ employment contracts are held by third-country nationals, a figure in line with the EU average. The most represented nationality is neighbouring Morocco at 27%, followed by Ecuador and Peru, two geographically distant countries but favoured by a common language and close diplomatic and economic ties. Bilateral agreements for the recognition of driving licences are in place, but it is often still necessary to obtain the Driver Certificate of Professional Competence in Spain, involving additional time and costs.

In Italy, the limited number of attestations, 2,619 at the end of 2022, indicates comparatively low reliance on non-EU drivers in international transport compared with the main operators in Eastern Europe. This may reflect a smaller presence of large fleets consistently engaged in international traffic or a different market structure, with a greater share of small and medium-sized undertakings operating mainly at national level. Looking ahead, however, the combination of an ageing workforce and competition from “facilitator” countries could reopen the question of the Italian system’s attractiveness for third-country drivers.

The prevailing nationalities in the European market largely reflect Poland’s weight, as it predominantly employs drivers from countries further east in Europe. In 2023, of the attestations issued in Poland, 88,923 concerned Ukrainian nationals, accounting for 55% of the national total, and 56,256 Belarusian nationals, equal to 35%. However, new recruitment pools are emerging, including India with 1,457 attestations and the Philippines with 1,288, signalling a gradual diversification towards Central Asia and South-East Asia following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which slowed inflows from that country. The report concludes that the integration of non-EU drivers is no longer a choice but an economic necessity, which nevertheless requires strong harmonisation at European level to remove administrative bottlenecks and ensure fair and safe working conditions.

M.L.